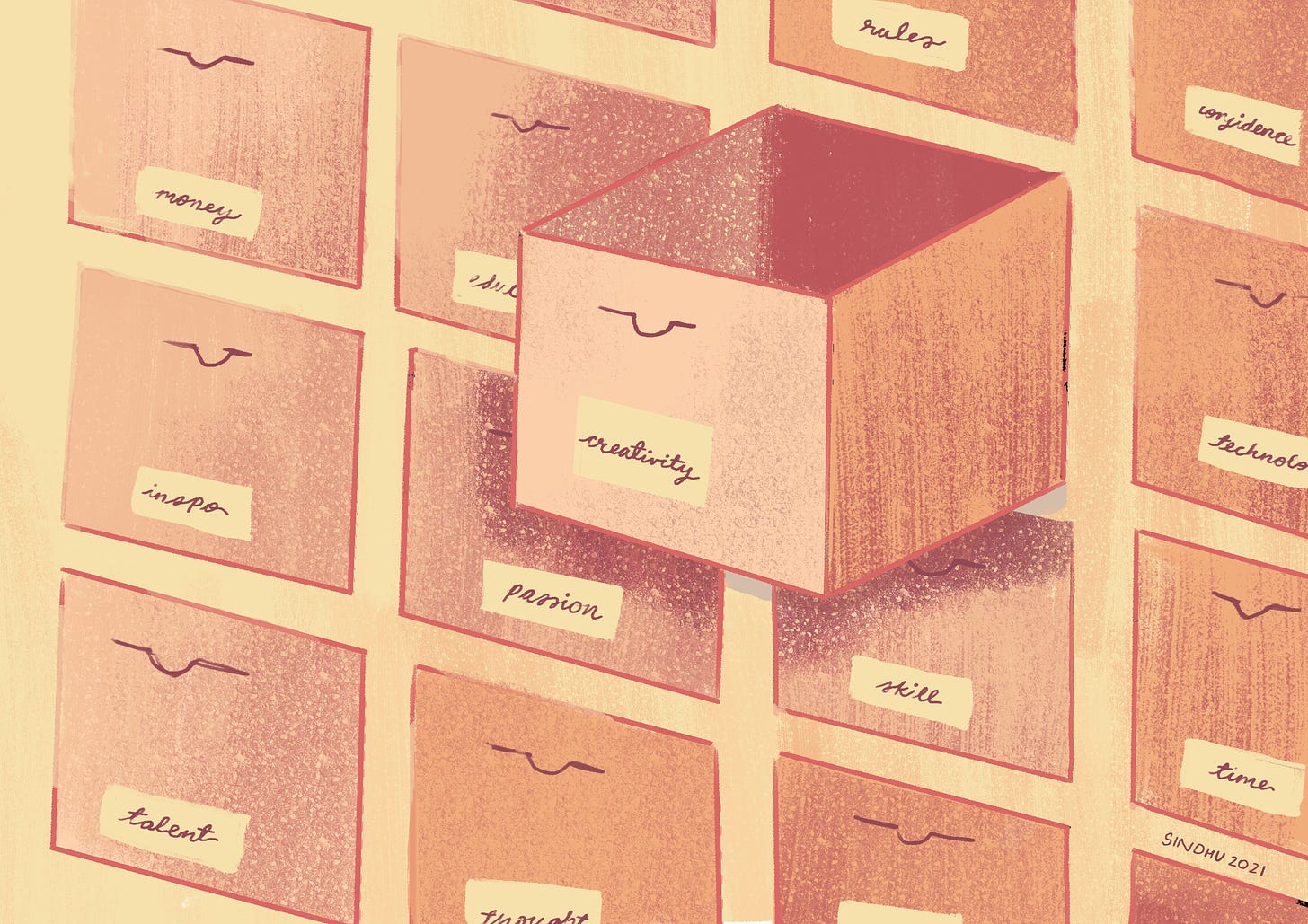

#24: The anatomy of creativity

Peeking under the hood with Tchaikovsky, van Gogh, Brontë and more

Happy new year, readers! Here’s wishing for a joyous, fulfilled, and safe 2022 for all of us.

I've been creating for a long time and I would be lying if I said I’ve never wanted to peek under the hood to see how creativity works. At the same time, I'm in awe of this mysterious force that pounds out words one time, leaves me tongue-twisted the next.

It isn't just me. Historians and aspiring creators have poked, prodded and shoved the notion of creative inspiration under the microscope for centuries. Creators and productivity gurus have tried to reverse-engineer the workings of creativity to arrive at a formula that works.

But the creative process isn’t an expertly-built mechanism that goes one way and one way only. Studying creatives across decades shows us that inspiration is only one part of a long and often challenging process — that of turning the germ of an idea into a vision, a prototype closest to your vision, and the final fruit of your labour.

Join me in an exploration of the journeys that some of our most lauded creatives took to make masterpieces.

Of being hit by inspiration

It's amazing how, across disciplines, creators describe inspiration pretty similarly: as an unpredictable, almost supernatural phenomenon.

Russian composer Tchaikovsky wrote in a letter to his intimate friend and patron Frau von Meck:

"The germ of a future composition comes suddenly and unexpectedly."

Vincent van Gogh describes it as "a terrible lucidity" during which "the picture comes to me like in a dream".

For yet others, inspiration feels as though a muse is using them as a mouthpiece. A feeling of divine absorption takes over; output is often feverish like it was with William Wordsworth (as explained by Dorothy Wordsworth):

"William wished to break off composition, but was unable, and so did himself harm".

We often hear about creatives looking bright, almost angelic as if their inspiration lit them up from the inside. It sounds a bit obtuse, but there are records of inspiration having noticeable physical effects on the ones whom it strikes. In Charlotte Brontë, for example, "a light would shine out as if a spiritual lamp had been kindled".

Since inspiration comes and goes on its own schedule, many famous creatives advocate noting down an idea before it is diluted or lost. If a lyric happened upon Alfred Lord Tennyson but "he did not write it down on the spot, the lyric fled from him irrevocably". It didn't matter what time of the day (or night) it was — an idea once arrived needed to be recorded instantly.

What happens when inspiration doesn't flow? There's a curious procedure for that too, for certain people of genius: to lose themselves in the works of other geniuses.

From inspiration to vision

Depending on the temperament of the creative, there are often two divergent approaches they will take. There’s the one-subject process, which is what it says on the tin: focusing one subject until all the juice is out. The creative is entirely absorbed in building up an idea for hours on end, walking, dining, and sleeping with it until it is complete. Dickens describes the new idea as being "everywhere—heaving in the sea, flying with the clouds, blowing in the wind..."

But another set of creatives swore by the complete opposite method: laying work aside to mature. You rough in the outlines and then, as Kipling advises, "let it lie by to drain as long as possible". While the ideas marinate on paper, they also float about in one's mind, stacking and conjoining to form a network of thought that some might've missed if they hadn't taken a break.

What one does during the marination period can vary, but popular advice from studying creatives seems to be: keep several subjects on hand at the same time. Since the mind may become dulled by spending too long on one subject, a change (or a bunch of them) might just help it see more clearly.

When it comes to actually putting in the work, some creatives wait for a definitive call, where sentences flow into each other and the picture almost paints itself. That said, others preferred everyday discipline over being captured by a whim. Flaubert and the likes put in a set number of hours every day to make their mind and imagination more supple. As Tchaikovsky beautifully puts it:

"We must always work and a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood. If we wait for the mood, without endeavouring to meet it halfway, we easily become indolent and apathetic. We must be patient, and believe that inspiration will come to those who can master their disinclination."

Years later, Picasso would unintentionally echo this sentiment, saying:

"Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working".

Bodily posture and environment are important factors in the creative process. When we conceptualise what working as a creative looks like today, we often think of the basic tools of our trade: sitting at a desk for writers, before an easel for painters, straddling an instrument for musicians.

Many creatives, though, were prone to ruminating over their ideas while in bed or pacing back and forth, wearing their carpets down. Beethoven "worked while walking"; Adam Smith paced the length and breadth of his room. Goethe, refreshingly, composed music on horseback.

Music historian Rosamund Harding describes the true creative—novelist, musician, poet or artist—as a discoverer. They follow the natural path of an idea, occasionally exercising judgement to prune a branch here or trim a shoot there but overall sticking to the main branch.

It reminds me of a quote often attributed to Michaelangelo:

"I saw an angel in the marble and carved until I set him free."

Regardless of how we get there, the creative’s goal is to find the final result —the painting, the music, the novel, the sculpture—in the stone.

It is the creative's role, in the process of taking inspiration to fruition, to chip away every chunk of stone that doesn't look like David.

If you enjoyed reading this and would like to share a part of it online, please tag me (@sindhusprasad on Twitter) so I can thank you right back. And if you know someone who’d enjoy reading this issue, please forward it to them, perhaps with a note to say, “I’m thinking of you”. 💌