Performing alchemy in the kitchen

When you think about it, kitchens are mad scientist laboratories

This is the second planned essay in Volume 1: Daily pleasures, inspired by the little things we take for granted that fundamentally shape the way we think and live.

I moved to England when I was 21. It was my first time living away from my home country, alone, for longer than six months. As I drew closer to my departure, I began spending more time in my mother's kitchen, watching the way she cooked — not to be there for a taste test this time, but to uncover the Magician’s secrets. Why did she pour four cups of water over the rice instead of three? How did she decide which veggies to fry first? How many whistles until she whisked the pressure cooker off the stove?

In a few days, I memorised all the steps to make some essential Indian dishes: rasam to go with steamed rice, palak paneer for roti, khichdi to eat if I fell ill. My knowledge of pasta and egg recipes thus supplemented, I hopped on that plane, paying a 200-dollar fee for overweight suitcases packed with pots, pans and pressure cookers from home. I clung to them like they were imbued with magic — or my mother’s experience. Whatever it was, it worked. With my tools from home, in a kitchen meant for 8, I came into my own.

Cooking connects people across time and space and is inseparable from our creaturely existence. But, like walking, not all cooking is the same.

Cooking to eat means being economical and calculative — evaluating what’s in the fridge, making do with replacements instead of running to the store for that perfect ingredient, and trying to minimise the number of dishes and tools we use to spare our future dish-washing self. It means accepting that some dishes have nine lives and that some ingredients are like a little black dress, suitable for anything. It means balancing how it looks with how much it costs.

Cooking to feed, on the other hand, requires many more considerations. Cooking for a child is not the same as cooking for an adult, for a picky eater, or for a lactose-intolerant person. The cheese that is Kryptonite for my sister is poison for me. My biryani now comes in three spice levels: Hater, Tolerant, and Spice-ophile.

When cooking to feed, there's cooking for labour and cooking for love. The former I've seen happen in kitchens run by women who've been forced into cooking to feed by patriarchal expectations. They tend to finish off all cooking for the day in the morning, choosing dishes from a mental list and whipping them up with practised indifference. Cooking for love, on the other hand, takes the shape of my 90-year-old grandfather, preparing my favourite dish with a toothless grin. Or my friend, making spaghetti for dinner and setting aside a generous cheese-less portion for me. Sometimes, labour is love.

I do, however, hear the naysayers protesting. Yes, I like to cook, they say, but I like to cook for others, to give my friends pleasure. Why would I want to go to all that trouble just for me? My answer is: If you like good food, why not honour yourself enough to make a pleasing meal and relish every mouthful?

— Judith Jones, The Pleasures of Cooking for One

So much of the cooking we do today is either performative or, on the other side of the spectrum, completely automated. We tend to view cooking as a chore, one more daily duty in a stretched-too-thin life. We supplement hours of cooking with podcasts, phone calls, a few episodes of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, anything to take away from the tedium. We think, "it's not supposed to bloody look like this. It's supposed to look pretty." Small wonder that there's been a dramatic drop in home cooking over the last 50 years but, weirdly, an increased interest in cooking as a spectator sport. We aspire to create the perfect bowls we see on Instagram and feel disappointed when we fall short.

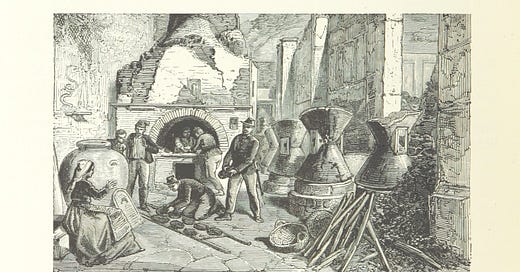

When we're caught in the weeds like this, worrying about the presentation or if three tomatoes are one too many, we forget that three times a day we perform one of the oldest forms of alchemy. We transform what the Earth gives us—and what we make—into more concentrated forms of nourishment and pleasure.

Left alone, a head of cabbage molds and decomposes. It becomes rotten, inedible. But when brined and stored, the course of its decay is altered … It exists in time and transforms.

— Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart

In almost every dish, there's a story nestled with the ingredients. It feels appropriate that, in ancient Greece, the word for “cook”—mageiros—shares an etymological root with “magic.”

Cooking isn’t always about presenting the fanciest meal, the most peculiar gastronomy that lingers in the mouth and the mind. The pressure to cook gram-worthy food takes away from the truth that even the simplest of foods can be the most soul-filling. The pressure to meal prep and plan weeks ahead takes away from the presentness of watching the sauce boil or eating bent over the stove, straight from the pot, because the aroma pulled you in.

No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin.

— Marcel Proust, À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu

Cooking, at its core, is a sensual experience. It is a whirlwind of aroma and sound, texture and taste, anticipation and vision. It can be visceral, which is why I've learnt to better appreciate instructions like "a dash of salt" and "a splash of wine". After a point, I no longer want to be told that I shouldn’t put a drop more — I want to. I want to see what happens. I want to create not a perfect recipe, but a Gross one:

A Gross Recipe is an expression of you: of the uniquely briny, spicy, bland, mushy, crunchy things at the core of you, in concentrations that the average person would find actively off-putting. In cooking for others, we are always making compromises... A Gross Recipe throws all of that out of the window; it is one of few chances that any of us get—in a kitchen or elsewhere—to be who we truly are.

— George Reynolds, Everyone Should Have a Gross Recipe

Sure, cooking can't always be Proustian. There are times when it's justified being categorised as a chore, another thing to tick off a packed to-do list. On occasion, you might forgo the process entirely, instead balancing a piping hot takeaway box on your knee while curled up on the couch, losing yourself in a TV show.

But once in a while, if we cooked to cook — not to feed, not to eat, not to create, not to invent — we would experience a freedom to observe. The way pie crust comes together perfectly during winter but wilts in the summer. The way strawberries are bursting with sweetness during warm summer months, and turn sour as we inch towards rainy days. The way, on some days, a warm bowl of ganji feels more like a balm than mere sustenance.

If we cooked to cook, we would retain agency over the process instead of outsourcing it. We would keep ourselves connected to the land and people that grew the strawberries for our dessert, and the spices for our gravy.

If we learned to cook to simply cook, we would probably enjoy it for all its natural, messy, curious joy. And, like any daily pleasure, we'd feel all the better for it.

I long to permeate the matter of this world: to become anchored to life by laundry and lilacs, daily bread and fried eggs.

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary